What is there to say about rifle cartridges that start in .300? The world is full of them. The .300 Winchester Magnum, the .300 HAM’R, the .300 Blackout. But in the beginning there was the .300 Savage. The Savage Model 99 in .300 savage was an attempt to get .30-06 power in lever action platforms. At that point, hunters and shooters made the .300 Savage one of the most popular big game cartridges. However, they shifted their preference to the suspiciously similar .308 Winchester when it hit the marketThe demise of the Savage 99 should’ve been the end of the .300 Savage. But some twenty-five years after its death knell, the .300 Savage is not quite dead yet. Here is the story of the .300 Savage cartridge and how it stacks up to the latest contenders.

The Savage 99: The Answer to an Unasked Question

Caption: The .300 Savage cartridge debuted in the Savage 99 lever action rifle. As seen in this Fall 1928 Sears catalog, it costed a pretty penny compared to the alternatives.

The Savage Model 1899, later shortened to Model 99, is lauded as a time-proofed lever action that deserved to live. Most lever actions use blunt-nosed bullets in tubular magazines to avoid primer contact. The Savage 99’s rotary box magazine allowed it to use spitzer bullets, which are more aerodynamic and have better sectional density. Though later chambered in .308 and .243, the Savage 99 wasn’t designed to solve an ammunition problem. When Savage introduced the rifle in 1899, it came in .303 Savage and .30-30 Winchester, both using round-nosed bullets. Savage also offered the rifle in older black powder rounds like .32-40 and .38-55. Militaries closely guarded the first spitzer rounds, which France publicly revealed in 1903. Germany quickly followed suit and the United States went to a spitzer with its .30-06 cartridge.

But once the technology was out there, the 99 aged well and soon chambered in rounds like the .22 Savage Hi Power. Savage added the .250 Savage to its portfolio in 1915. In 1919, it discontinued the old black powder rounds and introduced the new .300 Savage cartridge the following year. The .300 Savage would quickly become the most popular chambering in the Savage 99 and quickly grow on other platforms. But how did the .300 Savage come about?

The .300 Savage Cartridge Explored

Caption: From left to right: .300 Savage, .308 Winchester, .30-06

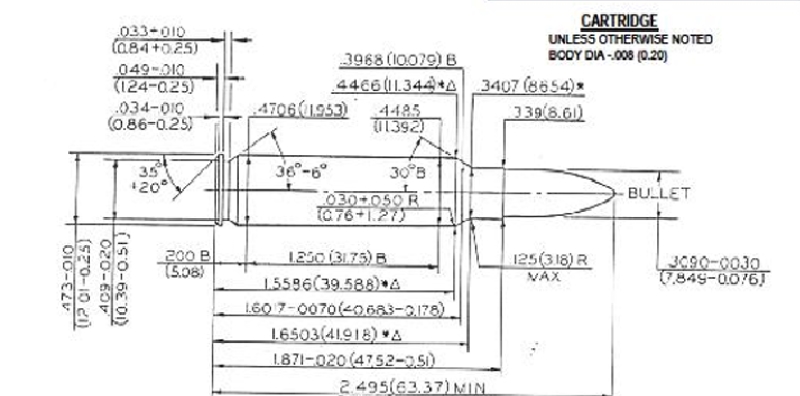

Savage had a leg up in development with the excellent .250-300 or .250 Savage cartridge. Savage debuted the .250 in 1915 and marketed it as the first cartridge to reach 3,000 feet per second. It featured a shortened .30-06 case necked down to .25 caliber. The .300 Savage, .250 Savage, and .30-06 have the same exact case-head diameter. All Savage had to do was neck it back up to .30 caliber to have a winner. This new cartridge had a stout 1.6 inch case with an abrupt 30 degree shoulder similar to the later 6.5 Creedmoor.

300 Savage vs 30-06

In terms of performance, the .300 Savage did not quite measure up to the .30-06. The original 180-grain spire point load matched the 173-grain boat tail .30-06, but at 2,400 fps compared to the .30-06’s 2,700 fps. It surpassed the .303 Savage and .30-30 Winchester, whose 170-grain round-nose bullets reached only 2,100 fps. The .300 Savage 150-grain load hit 2,600 fps, 200 fps slower than the M2 ball .30-06, but 300 fps faster than its lever-action competitor.

The .300 Savage cartridge was picked up by the likes of Remington and Winchester. The Remington 721-725 bolt action rifles, the forefathers of the Model 700, came in .300 Savage. The legendary Winchester Model 70 was also available in the cartridge, as was their Model 760 pump action rifle.

Over thirty years passed since the .300 Savage debuted. The first ball powders had since come onto the market and semi-auto rifles were beginning to make in-roads in the light rifle category dominated by lever actions. For Winchester, it was easier to make the .308 Winchester from the ground up to suit the task at hand and in 1952, the round made its debut.

300 Savage vs 308 Win

The .308 Winchester ultimately marked the end of the .300 Savage. Based on the same .30-06 case as the .300, the .308 featured a longer 1.71-inch overall length, a slightly longer neck, and a 20-degree shoulder for greater powder capacity. It could fire a 150-grain bullet at 2,850 fps, matching M2 .30-06 performance, but at higher pressures—62,000 psi compared to the .300’s 47,000 psi. New rifles like the Remington 700 and Winchester Model 70 were quickly chambered in .308, and Savage followed suit, offering the Model 99 in .308. The Model 99 remained available in .300 Savage until its discontinuation in 1999, ending its run after a century, though countless rifles chambered in .300 remain.

Caption: A SAAMI drawing of the specs of .300 Savage.

The .300 Savage Today

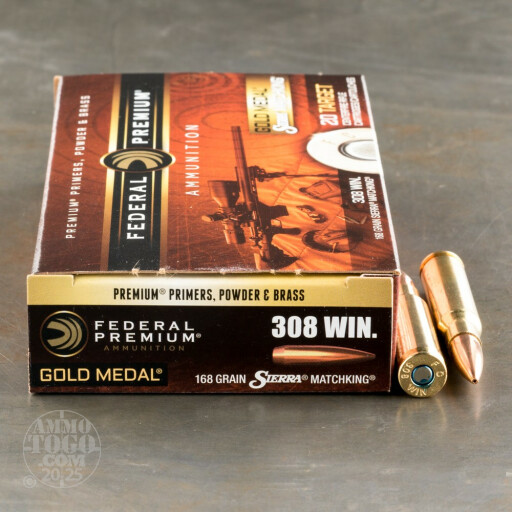

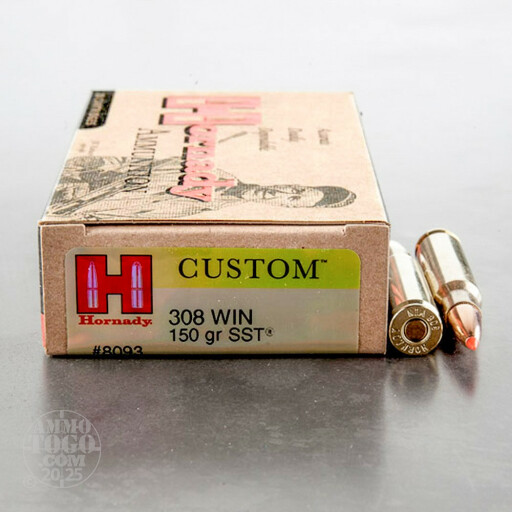

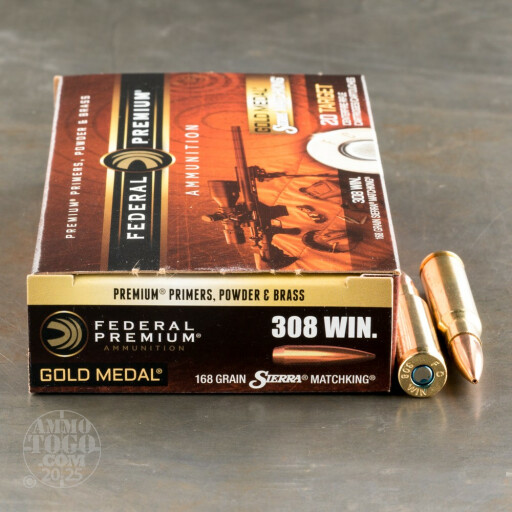

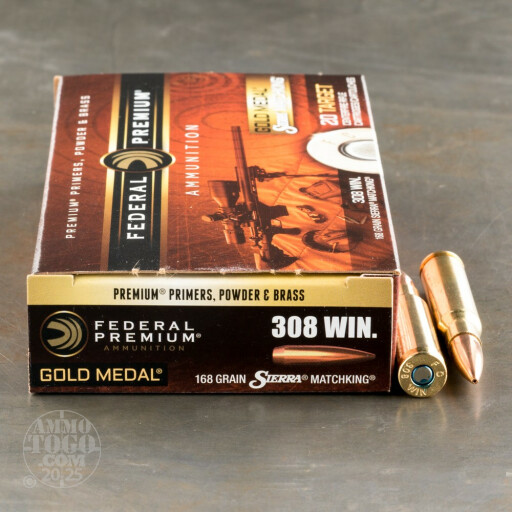

Over a million Savage 99s were produced, the bulk of which were in .300 Savage. That does not include the array of other rifles that chambered the round that are no longer being manufactured. The demand for .300 Savage is steady for shooters and hunters who field these aging long guns. As such, Federal, Winchester, and Hornady produce brief runs of the ammunition every year. Steinel Ammunition has recently announced the carrying of the round in 2025. Brass for the .300 can be readily made from .308 Winchester or 7.62 NATO. Identical .308 inch diameter bullets would be need to be paired.

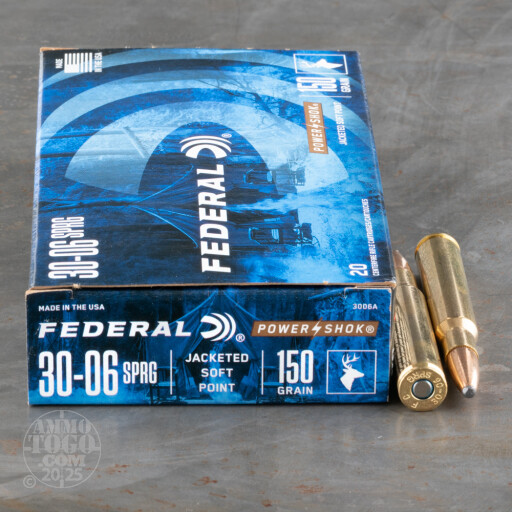

Winchester offers the round in a 150 grain Super X Power Point. Remington offers a 150 and 180 grain Core-Lokt load. Federal offers the same grain weights in their PowerShok line. The 150 grain loads have an advertised muzzle velocity of 2,650 feet per second. 180 grain loads nominally run at 2,350 feet per second. Hornady offers the .300 in their Superformance line with a 150-grain ballistic tip round at about 2,740 feet per second, ebbing ever closer away from .308 territory to .30-06 territory in the 21st century.

The Ballistics of the .300 Savage: How Slow is Too Slow?

Caption: My Savage Model 99 on the range.

As mentioned before, there are plenty of .300 Savage rifles out there waiting to be shot. But just how powerful is the .300 Savage and how does it perform? To answer that question, it is useful to compare it to more familiar rounds as a basis of comparison. Its main rival in the lever gun market was the .30-30 Winchester, which is still popular today. And the .308 Winchester effectively put the .300 Savage to pasture in the decades after its introduction. So I dusted off my recent acquired Savage 99 in .300 Savage, snapped up a Marlin 336 in .30-30, and a new production Stevens 334 in .308. I wrangled up a few different types of ammunition, packed my chronograph, and headed to the range to see what I could learn.

Caption: Lever action rifles in .30-30, like the Marlin 336, successfully competed with the .300 Savage due to their lower expenses and good performance at moderate ranges.

Historically and past my chronograph, the .300 is a shot across the bow of the .30-30. The .300 has the advantage of spire point projectiles with less drag and drop. 180 grain loads are nominally heavier and have a greater sectional density and ballistic coefficient than even 170 grain round-nosed .30-30. Out of my Marlin 336 with a 20 inch barrel in .30-30, I could get an average five-shot velocity of 2,318 feet per second across my chronograph with any of the 150 grain flat-point loads including Remington Corelokt and Winchester Power Points. Factory 24 inch barrel offerings clock out about 2,400 feet per second.

Next, I fired a few 150 grain loadings from the Stevens 334 across the chronograph. The Stevens is a budget bolt gun with a 20 inch barrel, four inches shorter than my Savage. But barrel lengths like 20 inches are typical for modern .308 like they are for modern .30-30 rifles. Even so, with the Remington ammunition I got an average velocity of 2,744 feet per second and with the Winchester, 2,812.

My Savage 99 in .300 Savage with a 24 inch barrel managed an average velocity of 2,792 using Hornady’s Superperformance ammunition. I achieved a average of 2,622 feet per second using Winchester’s 150 grain load, while the 180 grain round clocked in at 2,446 feet per second. Hornady’s load effectively duplicates .308 Winchester ammunition, with the conventional Winchester .300 Savage loads being one step below the .308 but a convincing step above rounds like the .30-30 Winchester.

Where’s The Drop? On The Range with the .300 Savage

Chronographs gives us raw velocity numbers and with bullet weight data, we can get an idea of energy foot pounds. But certain bullets do certain things during flight that simply do not show up here. The .30-30, .300, and .308 are all proven big game rounds within reasonable ranges, but one has to ask what a reasonable range is? In the thickets and swamps of my home state of Louisiana, 200 yards is a far shot. In the valleys of Colorado, 200 yards might be ranked as a midrange shot.

Caption: Even with its stock iron sights, this Savage 99 in .300 Savage is quite a shooter.

To that end, I shot my rifles at targets ranging from 100 to 300 yards to simply get an idea of their respective chances. I received the Savage 99 with an ill-fitted scope mount that I couldn’t zero correctly. So I reverted to the semi-buckhorn iron sights. The .30-30 and the .308 both have the option of a 3-9×40 Vortex rifle scope to aid me. Even so, at 100 yards, I turned in a better group using the Superperformance and Winchester Power Point 150 grain loads using the Savage 99 compared to the Marlin 336. The Winchester rounds printed an inch lower than the Hornady load, but I could get a 2-inch group with ease with iron sights, whereas the Marlin could accomplish the same with an optic using Winchester 150 grain flat points. The Stevens 334 managed an inch and a half using 150 grain Remington CoreLokt soft points.

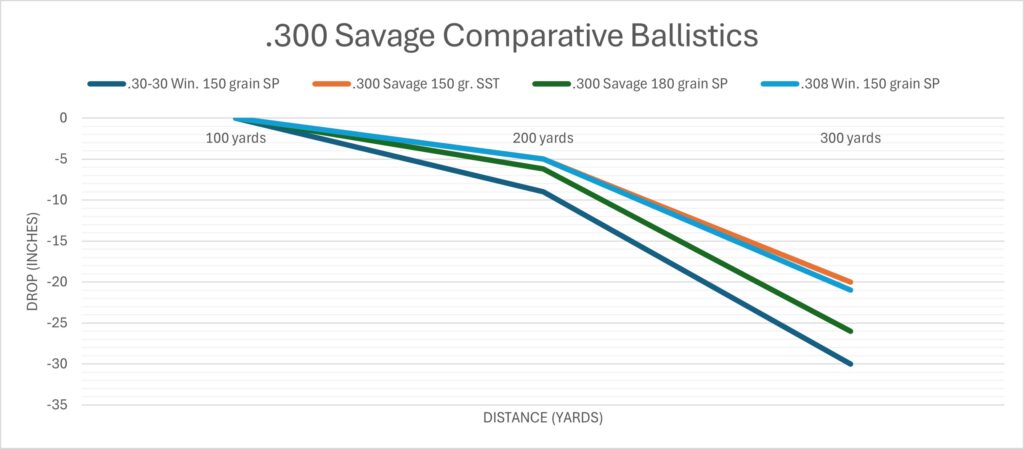

At 200 yards, the 150 grain loads from the .30-30 had dropped 9 inches. The .300 Savage Superperformance was down by five and Winchester 150 grain .300 was down by six. The Stevens 334 printed its rounds in the same spot as the Hornady round.

At 300 yards, the .30-30 has lost most of its pasta. The 150 grain Winchester load hit the bottom of the target thirty inches low. The Hornady load from the .300 hit 20 inches low, while the Winchester 180 grain load hit 26 inches low. The .308 Winchester performed a bit better. The Remington CoreLokt rounds from its 20-inch barrel hit 21 inches lower than the point of aim. This load gave excellent accuracy at that distance. I consistently got five rounds into a 5-inch group at that distance. The Savage scattered them into a foot-sized group.

An optic mattered in this test, but the .300 managed to outperform the .30-30 easily, even with stock irons.

.300 Savage ammunition may not be a modern hunter’s first choice, with no new rifles made and limited ammunition availability, but it’s far from obsolete. Millions of rifles remain in use, and the .300 can perform wherever a .308 can. Though its popularity has waned, the .300 Savage remains effective and might surprise you as a reliable hunting option.